New York Times August 14, 2005

By TERI KARUSH ROGERS

TO some, the Upper East Side is clean, prosperous and endowed with an enviable service culture that lubricates the lives of busy residents. To others, it is staid and prissy, the home of an uptight, white-collar ruling class.

But it's also a comparative bargain, and that singular fact, aided by more plentiful inventory, is luring those who would prefer to live elsewhere.

It's an odd concept to those who have lived in New York for more than a minute. Less than a generation ago, the Upper East Side was anything but a backup choice.

"For many years, the Upper East Side for most New Yorkers was really the best option, almost the only option," said Hall F. Willkie, the president of Brown Harris Stevens. "That, or certain parts of the West Side. That was true if you were buying something at the high end or if you were a young person coming in for the first time to New York. It was considered safe, and the place to be."

The change in perception, and in prices, is striking.

"I think the Upper East Side right now is undervalued," said Daniela Kunen, a managing director with Prudential Douglas Elliman.

Like many other brokers and buyers interviewed for this article, Ms. Kunen estimated that a dollar goes 20 to 25 percent further there than downtown or on the Upper West Side.

In some cases, that may be an understatement, according to numbers provided by Miller Samuel, a Manhattan real estate appraiser. As of June 30, the median price of a two-bedroom apartment on the Upper East Side was $1.13 million, compared with $1.34 million on the Upper West Side, $1.41 million in Greenwich Village, and $1.975 million in the SoHo and TriBeCa area.

Apartments have appreciated much less on the Upper East Side. From 2000 to 2005, the median price on a two-bedroom apartment there rose by 43.1 percent, compared with 76.9 percent in Greenwich Village, 79.5 percent in SoHo-TriBeCa, and 91.4 percent on the Upper West Side, according to Miller Samuel.

And that doesn't just pertain to the high-rise buildings east of Third Avenue. Even the grandes dames lining Fifth and Park Avenues lagged: over the same period, the median price of a two-bedroom co-op there rose by 36.3 percent, compared with 61.4 percent on Central Park West.

That could be in part because the Upper East Side is growing off a higher base than other neighborhoods that used to be considered cheap.

"It's sort of like comparing an emerging market stock against a Dow Jones industrial, where there's more inherent risk but greater return," said Jonathan J. Miller, president of Miller Samuel.

Now that the Upper East Side is looking like a bargain, it is starting to draw people who would have once considered TriBeCa or SoHo.

"The downtown loft market particularly fed off buyers that would have looked at the Upper East and West Sides," Mr. Miller said. "But now as price-per-square-foot metrics become more even, some of the flow has gone the other way."

He noted that a more diverse housing mix may explain some of the pricing disparity: for example, more two-bedrooms on the Upper East Side are co-ops of the 1950's and 60's white-brick vintage, while downtown, more two-bedrooms are located in pricey new condo buildings.

But value-savvy buyers aren't necessarily alighting with a bounce in their step.

"I really didn't want to live up there," said Lori K. Schwartz, 36, a consumer products marketer who wanted to remain near Gramercy Park, where she rented a studio. "I tend to go out more downtown, and honestly it wasn't that hip of a neighborhood."

Her search for a one-bedroom under $500,000 proved predictably fruitless below 23rd Street, said her broker, Christine Miller Martin of Warburg Realty Partnership. "Everyone starts out going downtown, but you can't really get a decent one-bedroom for under $700,000," she said.

"On the Upper East Side, you can find a comparable apartment in the half-million-dollar range. If you're not somebody who needs to be right next to the hip, happening restaurant and bar, the Upper East Side makes a lot of sense."

In June, Ms. Schwartz moved into the one-bedroom apartment she bought for $450,000 on 79th Street between Second and Third Avenues. "I love the fact that I'm near the park," she said. "To have that is key. The downside is I have to take cabs when I'm going out. But over all it's nice, it's pleasant, it's clean, convenient. I can see myself staying for a decent amount of time."

While SoHo, TriBeCa and the Village may be hip, the Upper East Side offers more substantial and varied inventory. At the end of July, the Corcoran Group listed 1,421 apartments for sale on the Upper East Side from 59th to 110th Streets, compared with 906 on the Upper West Side from 59th to 125th, 225 in Chelsea, 141 in TriBeCa and 115 in the West Village.

"You're able to choose from a much wider variety of buildings," said Michele Kleier, president and chairwoman of Gumley Haft Kleier. Like other brokers, she suggested that the area's classic strengths - schools, parks, playgrounds, services, cleanliness and safety - more than compensate for its slight heft on the hipness scale. "It's almost like the little black dress of real estate; it's always in style, it's always elegant, it's always appropriate," she said.

Of course, not every new arrival is willing to trade flip-flops for Ferragamos.

"The first six months, I was going nuts," said Jennifer S. Lee, 36, an architect who moved from Gramercy Park to 76th Street near Lexington Avenue. "I felt like I had to dress a lot less casually, No. 1, and much more conservatively."

It was one of several adjustments for Ms. Lee, who told a familiar tale of choosing the Upper East Side by default. In the fall of 2003, she and her husband began looking downtown for a two-bedroom under $750,000. The pair quickly downgraded their expectations from prewar to postwar, which led them uptown to the white-brick buildings east of Lexington Avenue.

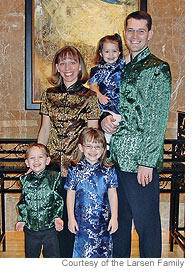

"Every time I went up there it was very homogeneous," said Ms. Lee, who is from Hong Kong and is married to a Filipino. "That kind of scared us a little bit. It was such a big difference. But the park is there."

A few months later, in the midst of an escalating market, they entered into a contract to sell their apartment. Their broker, Judith Thorn, an executive vice president at Warburg Realty, showed them a 1,400-square-foot apartment in a postwar doorman building on East 76th Street that was only slightly over their budget.

"I felt completely out of place," Ms. Lee said of her early months in the neighborhood. "I did feel like everybody was white, whereas downtown, it was really a nonissue. I still feel the difference but I've learned how to live with it." Out with her daughter, Chloe, now 2, she said, people occasionally mistook her for a hired caregiver, "especially when I wasn't as dressed up and not wearing a wedding ring."

"So here I was a professional in my mid-30's with an Ivy League education, and everyone thought I was a nanny," she said.

Though they paid less for an apartment than they would have downtown, Ms. Lee and her husband encountered another form of sticker shock. "It's at least 10 percent more expensive up here for laundry, for the corner Chinese restaurant, down to the nail salon. But the services are much better. I think they are more used to the people expecting the service. Everyone delivers."

Ms. Lee and her husband are far from alone in choosing space first, neighborhood second.

Two summers ago, Renee Litvak, a 29-year-old endodontist, and her husband began looking for a new three-bedroom condo on the Upper West Side. "Prices went up on the Upper West Side by 50 percent, and on the Upper East Side, 30 percent" that first year, Dr. Litvak said. They watched as one apartment they had rejected on Riverside Drive was flipped for 50 percent more a year later.

On the advice of their broker, Ms. Kunen of Prudential Douglas Elliman (who also happens to be Dr. Litvak's mother), the pair turned to the Upper East Side. Though competition was still intense, "it was certainly obvious there was more available and you certainly got more space for the money," Dr. Litvak said. They quickly found a three-bedroom, three-bath, four-year-old condo at 78th Street and Third Avenue, where they will move later this summer from their rental at West End Avenue and 63rd Street. Without raising their budget, "we were able to increase the size of our apartment by about 30 percent," Dr. Litvak said. Though it was not their first choice, they are hopeful about the neighborhood.

"We perceive our neighborhood to be young families, lots of good restaurants, lots of amenities," she said, drawing a comparison with the Upper West Side. "Third Avenue going east, there's lots of families and restaurants. If you go west toward Fifth Avenue, it gets desolate and deserted at night."

While many reluctant settlers gravitate toward the East 60's and 70's between First and Third Avenues, others venture farther north or east.

Mitchell Brown, a 52-year-old sales agent with Bellmarc, sold his home in Muttontown, on Long Island, last year. A native Upper West Sider, he intended to buy a one-bedroom there, near the stables at Claremont Riding Academy on West 89th Street, where he rides twice a week.

"When I was a kid living on the West Side, it was always a more bohemian, more intellectual kind of place," Mr. Brown said. But he couldn't find what he wanted in his price range. "When my broker said to go to the Upper East Side, I said, 'No, it's more conservative, less artsy.' " Then he fell for a 28th-floor, 820-square-foot condo with a 12-by-12-foot terrace on 80th Street near First Avenue.

His first impression of the neighborhood? "It's very residential, somewhat boring, and not downtown, but at my age and lifestyle, it's nice," he said. "I come home, I have a million restaurants to go to, two parks, and I can walk to my horses at Claremont if I want to."

A few blocks north, Julia Stone, 31, who works in the fashion industry, bought a $350,000 jumbo studio late last year after being priced out of "younger, hipper" SoHo. Like Mr. Mitchell, she said she was pleasantly surprised by her new environs on 86th Street near First Avenue.

"It's really quiet," said Ms. Stone, who found the apartment with the help of Mitzie Lau, a broker at Corcoran. "When you're with people all day and talking to people all day, you start to need a little solitude."

Yet, Ms. Stone said, "Everything I need is up here; independent bookstores, movie theater, everything." Public transportation is the biggest drawback; to get to her job in the garment center, Ms. Stone takes the bus to the Upper West Side, where she transfers to a downtown train.

Bad transportation is the least of Eyal Vadai's complaints about life in the northern reaches of the Upper East Side. "I honestly feel like I'm in Guam," said Mr. Vadai, 28, an Internet marketing entrepreneur. About 18 months ago, working with Julie Friedman, a senior associate broker at Bellmarc, he bought a one-bedroom fixer-upper on 91st Street near Third Avenue for $215,000. Taxis are scarce, he said, and cost $12 to take downtown, where he likes to eat at restaurants with his fiancée, Danielle Goffin, 27, a talent negotiator.

Speaking from his office on West 38th Street about the culinary desolation surrounding his apartment, Mr. Vadai noted: "There I have a kosher pizzeria and a Brother Jimmy's. I'm isolated from everything. I go there to sleep, to live, and nothing else. So I spend most of my time outside of the apartment." With a $60,000 renovation completed, he plans to sell early next year, and keeps a calendar on his computer marking off the days until the second anniversary of his closing, after which his profit will be excluded from taxation.

On the lower end of the Upper East Side, recent empty-nesters Patrick and Carolyn Dolan are preparing to take up residence in a freshly minted, $5.4 million three-bedroom condo at One Beacon Court on 58th Street opposite Bloomingdale's. Eighteen-year denizens of a 35th-floor condo near Lincoln Center, they spent the last six years hunting for a bigger Upper West Side place with equally commanding views.

"We were leaning toward Central Park West, but the more we looked, the more we found that the buildings were not offering what we wanted at a price we thought was reasonable," said Ms. Dolan, a principal at an investment management firm. Of the new apartment, shown to them by S. Jean Meisel, a senior vice president and managing director at Brown Harris Stevens, she said, "When we saw it, we loved it."

But what about the neighborhood? "We always wondered, why do we want to be by Bloomingdale's?" Ms. Dolan said. "But finally, after we saw so many things that were not inviting compared to what we lived in, we thought we might as well give it a try."

Ms. Lee, the architect who moved to East 76th Street despite misgivings about the area's homogeneity, is more sanguine these days. She has formed a close-knit circle of friends, though fewer of them work in creative fields than her former compatriots. "I'm very happy where I am; I love the park, and I love my friends," she said.

Still, she allowed, she wasn't sure if she would do it over again. "I might have looked a little harder downtown," she said.